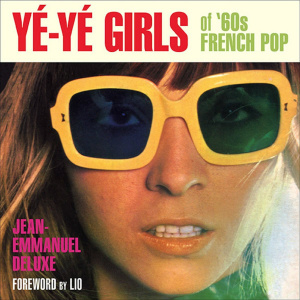

Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe - Yé-Yé Girls of ‘60s French Pop (Feral House)

French pop culture study uncovers much of this little documented world, but leaves you hungry for a whole lot more

Released Jan 23rd, 2014 via Feral House / By Larissa Wodtke

In many ways, Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe’s Yé-Yé Girls of ‘60s French Pop successfully fills an information gap in pop music writing. Looking at Deluxe’s bibliography for this book, the necessity for an English-language book documenting the ‘60s genre becomes apparent. Whilst there’s been an online presence of yé-yé history in the form of English-language music blogs and even a French Internet radio station devoted to the music itself, there hasn’t been a monograph dedicated to exploring the primarily French genre for the English-speaking world. Deluxe makes it quite clear that he writes from the position of fan, so it is no surprise that the book is quite positive and enthusiastic towards this female-dominated Gallic bubblegum music (there’s a liberal use of the exclamation point). He writes in a journalistic style that favours fragmented features rather than a sustained narrative about the subject; the book is thus helpfully organised into chapters and subsections that clearly signpost the ground covered, including Serge Gainsbourg’s involvement in the genre, the four most significant yé-yé stars, the British singers who sang in the style, the media that recorded the genre and transcripts of current interviews with several of the ‘60s yé-yé performers. With its glossy, playful feel, the design of the book reflects Deluxe’s light writing style along with the yé-yé aesthetic itself; the design, complete with columns and beautiful full-colour image spreads, also echoes the pop mag culture of the period.

In many ways, Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe’s Yé-Yé Girls of ‘60s French Pop successfully fills an information gap in pop music writing. Looking at Deluxe’s bibliography for this book, the necessity for an English-language book documenting the ‘60s genre becomes apparent. Whilst there’s been an online presence of yé-yé history in the form of English-language music blogs and even a French Internet radio station devoted to the music itself, there hasn’t been a monograph dedicated to exploring the primarily French genre for the English-speaking world. Deluxe makes it quite clear that he writes from the position of fan, so it is no surprise that the book is quite positive and enthusiastic towards this female-dominated Gallic bubblegum music (there’s a liberal use of the exclamation point). He writes in a journalistic style that favours fragmented features rather than a sustained narrative about the subject; the book is thus helpfully organised into chapters and subsections that clearly signpost the ground covered, including Serge Gainsbourg’s involvement in the genre, the four most significant yé-yé stars, the British singers who sang in the style, the media that recorded the genre and transcripts of current interviews with several of the ‘60s yé-yé performers. With its glossy, playful feel, the design of the book reflects Deluxe’s light writing style along with the yé-yé aesthetic itself; the design, complete with columns and beautiful full-colour image spreads, also echoes the pop mag culture of the period.Deluxe does some promising work towards extrapolating out of the genre proper and into other geographical areas and genres, including psych-folk and freakbeat. He also gestures toward a cross-cultural context, but never quite articulates it. Whilst it was definitely interesting to read about how yé-yé manifested in later French pop music, it would have been fascinating to know more about how yé-yé influenced shibuya-kei and was ironised in late-twentieth-century acts like Stereolab and Saint Etienne. In fact, the main criticism to be levelled at this book is its wide-ranging, but superficial treatment of the content. There’s the frustrating sense that the author could write more about the political importance of a seemingly “apolitical” genre and the cultural significance of its adaptations and permutations, but he simply doesn’t. This tension between ostensible, naive glibness and a more complicated undercurrent at the heart of both the yé-yé genre and this book never resolves itself.

The one-page conclusion attempts to pull back briefly from all of the glamorous fun and fannish celebration with some awkward references to Guy Debord and the “society of the spectacle,” perhaps in a last-ditch, misguided effort to insert some critique and deeper meaning. But it’s an understatement to say that this leftist philosophy out of leftfield is too little, too late. Despite stating “pop music can tell us more than many a sociological essay” in his introduction, Deluxe does little analysis of sociological context for most of the book. He largely misses the opportunity to problematise the gender dynamics of yé-yé and to explore a more nuanced relationship, or perhaps antagonism, between this genre and the radicalism of ’68 (May ’68 crops up a number of times, but is either mentioned in passing or dismissed). Of course, a sustained engagement with the sociocultural context of the genre may seem at odds with the overall tone, and perhaps it’s asking too much of this particular book to be more critically comprehensive than it is. In short, Yé-Yé Girls of ‘60s French Pop provides a solid, but basic introduction to information about a truly interesting popular culture phenomenon; however, it ultimately serves only as a beginning, hinting at a conversation and demanding further in-depth analysis and valuable contextualisation. The prospect of a music critic with an intelligent, informed take on gender, politics and cultural studies building on this book for English audiences is an exciting one.

All Content RSS Feed

All Content RSS Feed

Follow Bearded on...